We went to Tokyo Disneyland for my birthday.

Apparently, it’s very unusual to find Mickey at Disneyland (other than in the parades and such), so we were very lucky to get this shot. Here you see Mickey with two girls dressed up in costumes for the Disney Halloween celebration that goes on throughout the month of October.

We got to ride the new Star Tours ride, which was probably the thing I most wanted to do this time around. While you wait in line, you walk through a “spaceport” and get to see various animatronic vignettes before the ride. The line for Star Tours is probably the most entertaining in the park, and possibly more entertaining than some of the other attractions.

Although you can’t tell in this static photo, the movements of C3PO were very dynamic and natural. Almost the entire ride, including the animatronic scenes, is in Japanese (so you’ll be missing out on a lot if you ride Star Tours in Japan and don’t speak Japanese), but I was impressed with the quality of the voice and the acting for C3PO. I believe the actor used is the same one who has been used for all of the Japanese dubs of Star Wars, and his timing was perfect, especially during the ride itself. Normally I hate Japanese voice overs, but I was perfectly satisfied with not being able to hear the original English thanks to the actor for C3PO.

A real-time computer-generated camera filter of guests walking by serves as a “security scanner” – the display on the screen at the back is also properly mirrored on the screen in front of the security droid.

The security droid has some basic recognition routines and will respond to what’s happening around it. Here he’s admonishing me for taking a picture (true story). We rode Star Tours twice and the second time, a bunch of guys were waving there arms at the security droid, to which he responded,”Yeah, I see you. Don’t worry. I’ll have my eye on you, no matter where you go.”

The “boarding gate” for the new Star Tours – mostly the same as the old one, with a new coat of paint and banks of 3D glasses for riders to pick up.

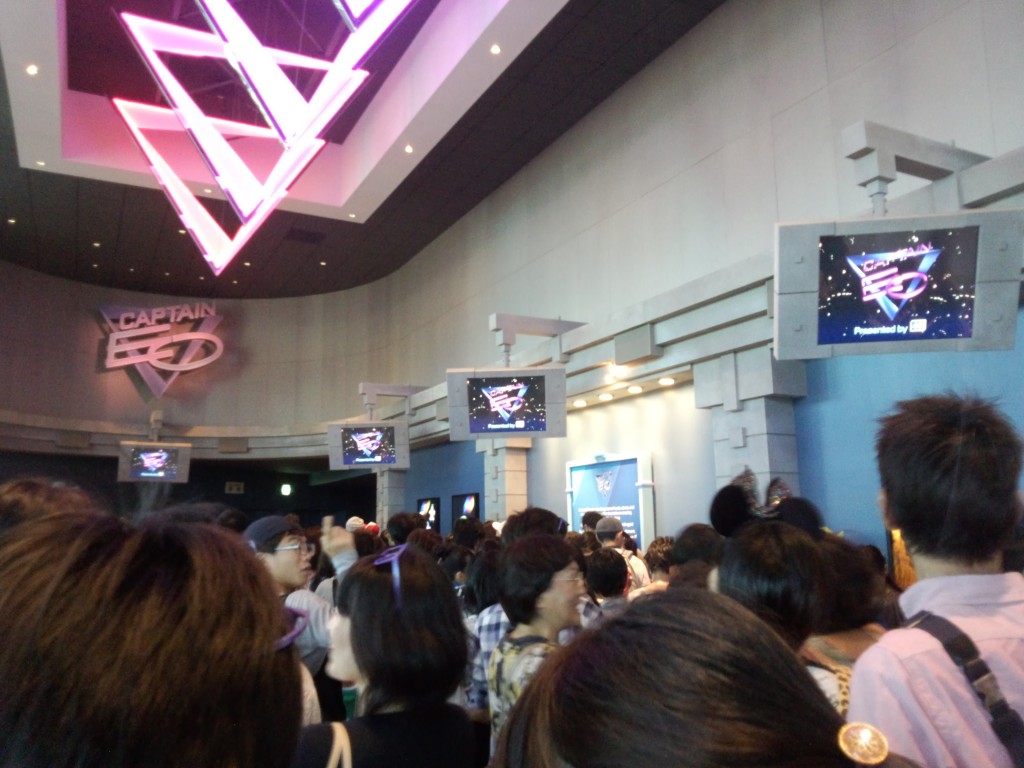

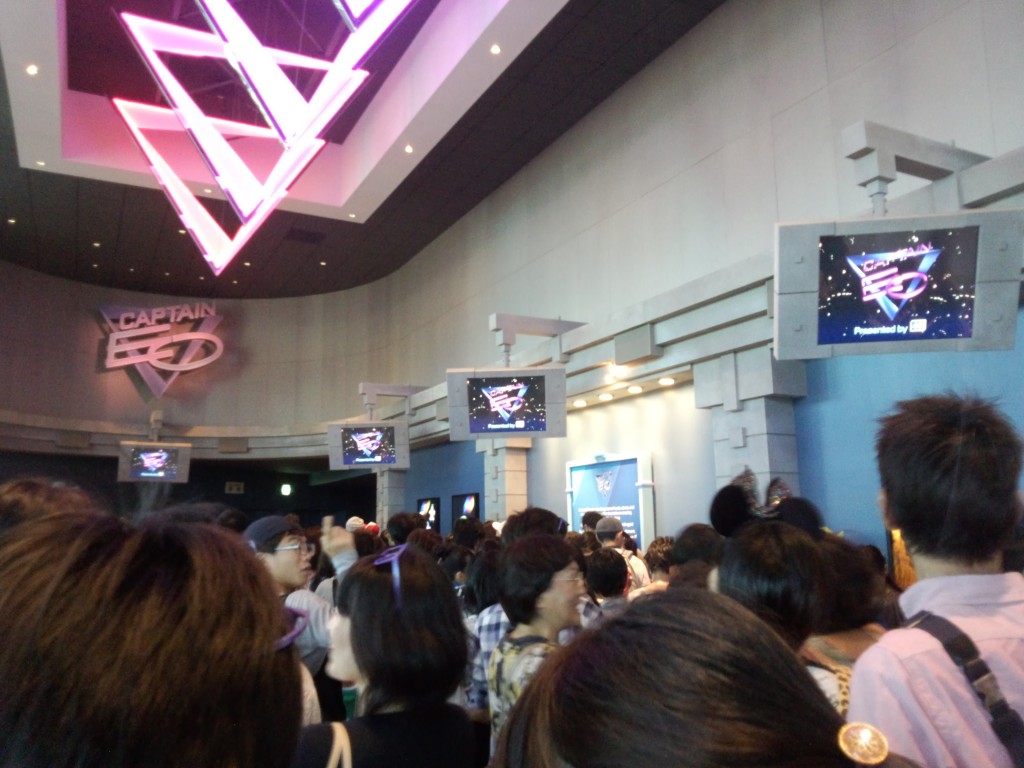

We also saw Michael Jackson’s Captain EO tribute, which was so 80’s it made my teeth hurt. Before you get to watch the movie, you have to stand in this hall and watch a cheesy making-of video. And I guess this is considered part of the attraction and not a line, but standing around watching small video monitors in a crowded room is not what you want to do when you’ve been walking around all day. However, unlike Star Tours, almost everything for Captain EO is in English. This short pre-show in the hall is in Japanese, but there are English subtitles, while the Captain EO movie itself is all in English, with tiny, hard-to-read (even for native speakers) Japanese subtitles in the right right of the screen.

It was also interesting to note the contrasts between EO and Star Tours. They’re both “4D” attractions, with effects occurring in the theater along with 3D visuals, but you could really feel how the technology had progressed. For example, the 3D glasses for Captain EO are this weird, continuous curved shape, from earpiece to glasses to the other earpiece, so you can’t really tuck the earpieces behind your ears comfortably like you would a normal pair of glass. Not only that, but the design manages to practically push the lenses into your eyeballs. The glasses for Star Tours were much more comfortable. Also, with Captain EO, they failed to take into account the fact that with 3D, you lose about half the light of the video because of the glasses, so the image was really, really dark and hard to see. Needless to say, Star Tours didn’t have this problem. Still, Captain EO was good, 80’s fun, although it pretty much hit my tolerance limit for interpretive dance.

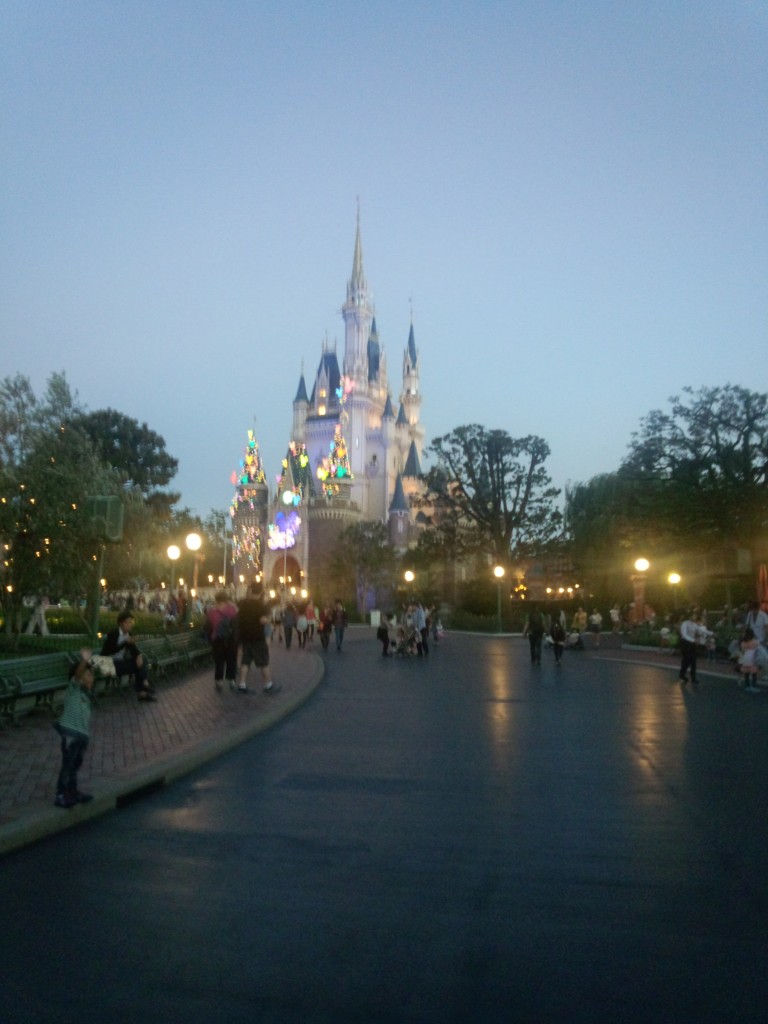

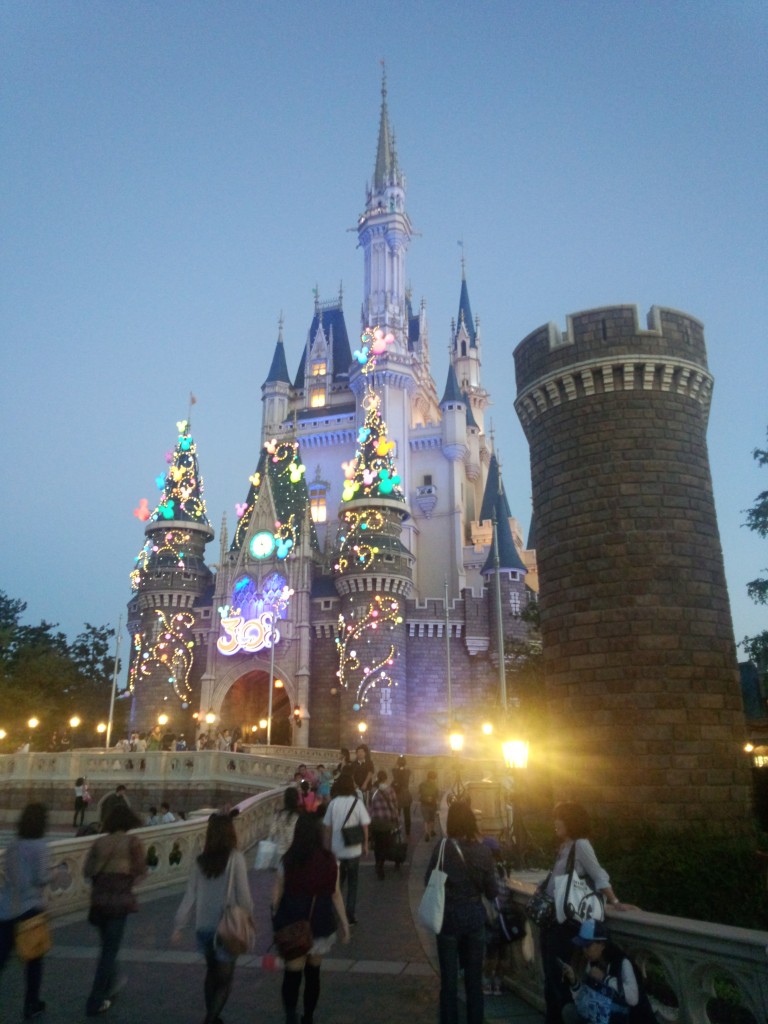

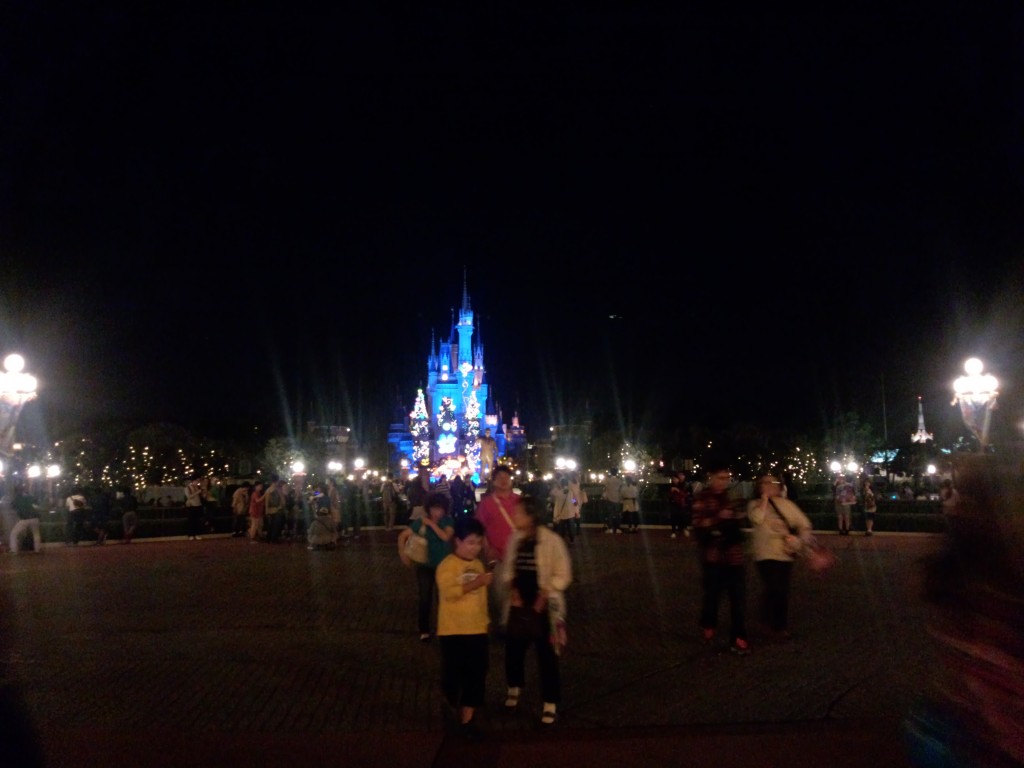

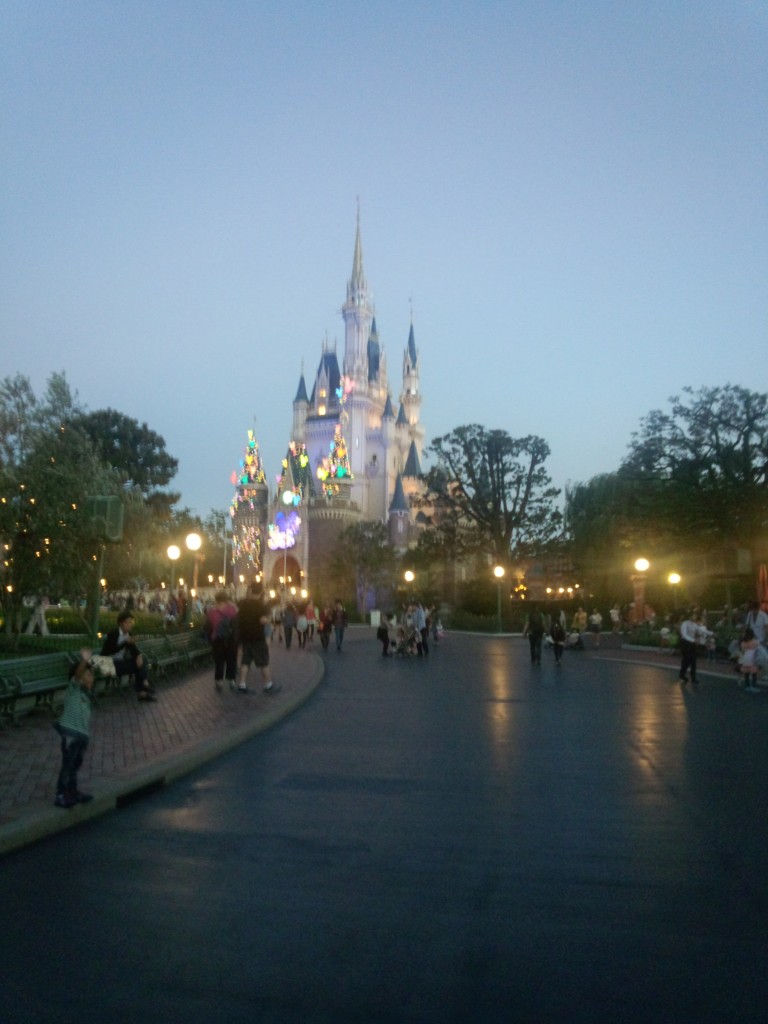

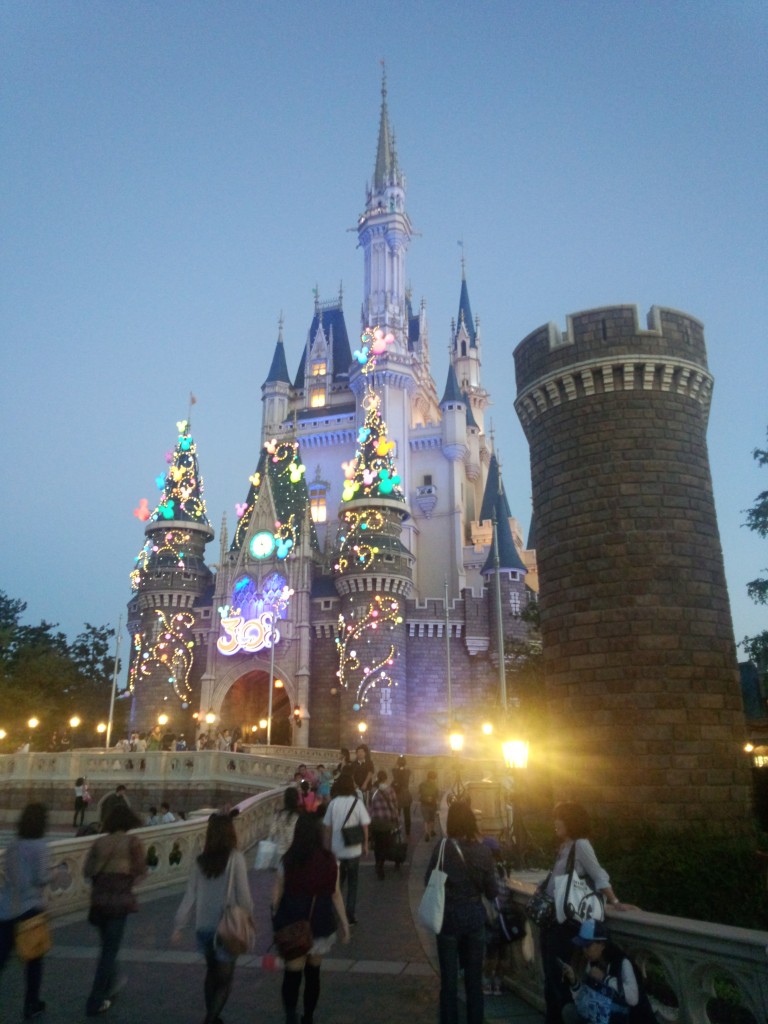

The castle is decked out for Tokyo Disneyland’s 30th anniversary celebration. 30th anniversary decorations were everywhere, which was kind of annoying because they took the place of many of the Halloween decorations that would normally be up this time of year. For example, there seem to be no Halloween decorations along this street, although there were the last time I went during Halloween. Perhaps they will put up more as Halloween approaches?

And this is when we went through that time warp – or I accidentally took a picture without noticing, one of the two.

I was rather satisfied with how these pictures came out and couldn’t choose which to delete.

They did a great job recreating the set of the movie for the line for the Monsters, Inc. Hide and Go Seek ride.

The detail on the desk was amazing. The sponsor for the ride is Panasonic, and the radio at the left actually had a little Panasonic logo on it, probably taken directly from some Panasonic production line.

Again, great detail, with a full garbage can in the back and work forms waiting to be stamped on the desk.

I imagine this section of the gift store is unique to Tokyo Disneyland – the senbei (rice cracker) section. Check out the awesome senbei-styled tin in the upper left, with Mickey-shaped nori (dried seaweed).

Even the Genie tins here are filled with senbei.

This Mickey-shaped cheeseburger was, unfortunately, the least satisfying meal we had at Disneyland – I was expecting a cheeseburger, but it tasted more like a Japanese hamburg steak.

Instagrammed.

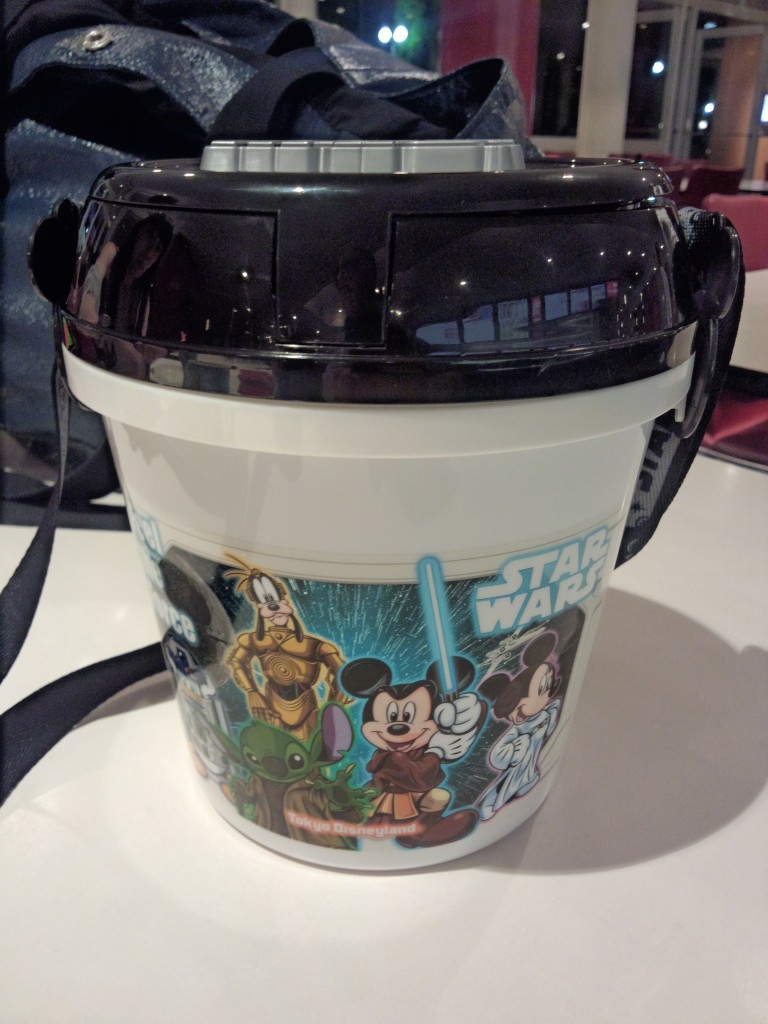

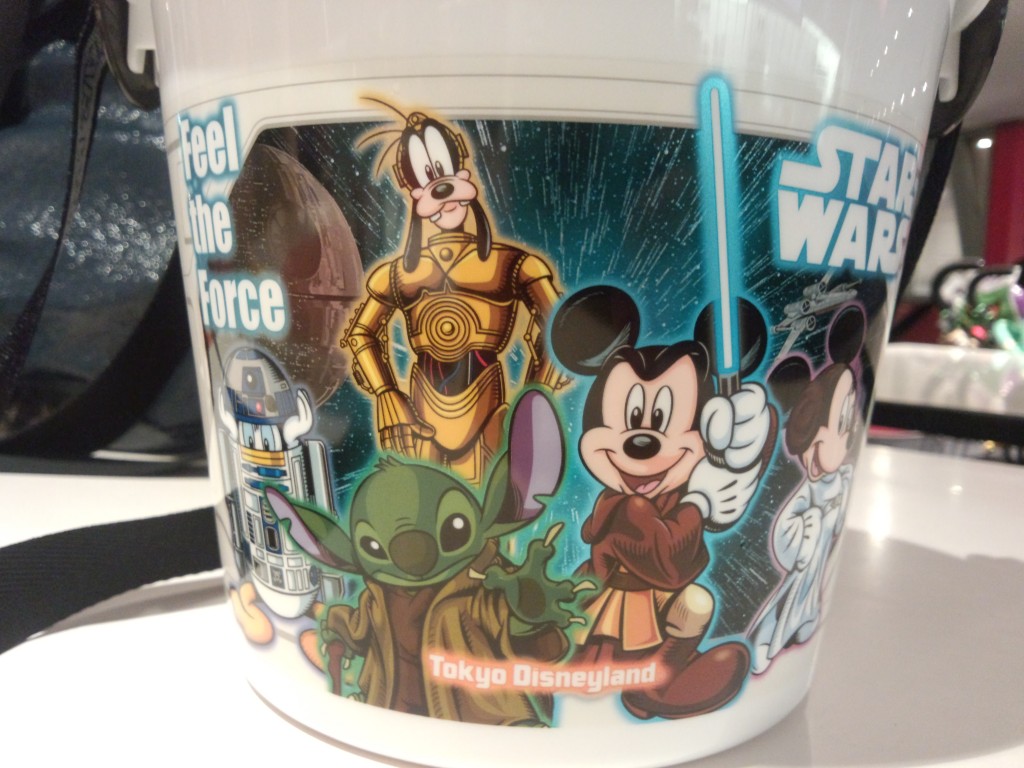

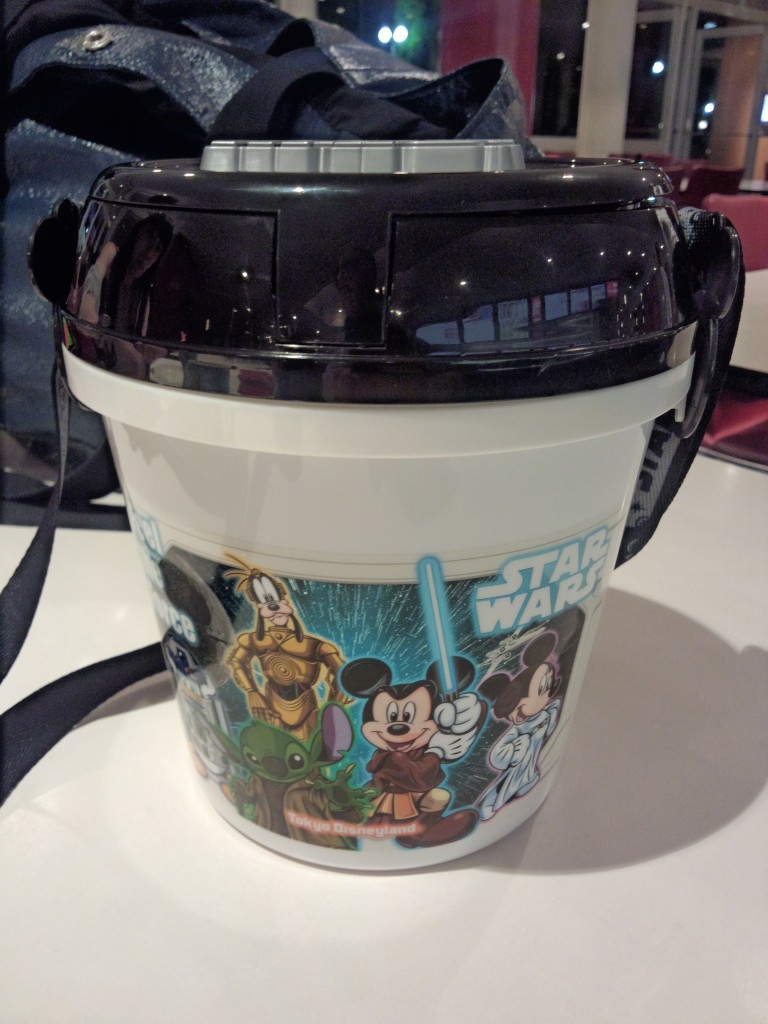

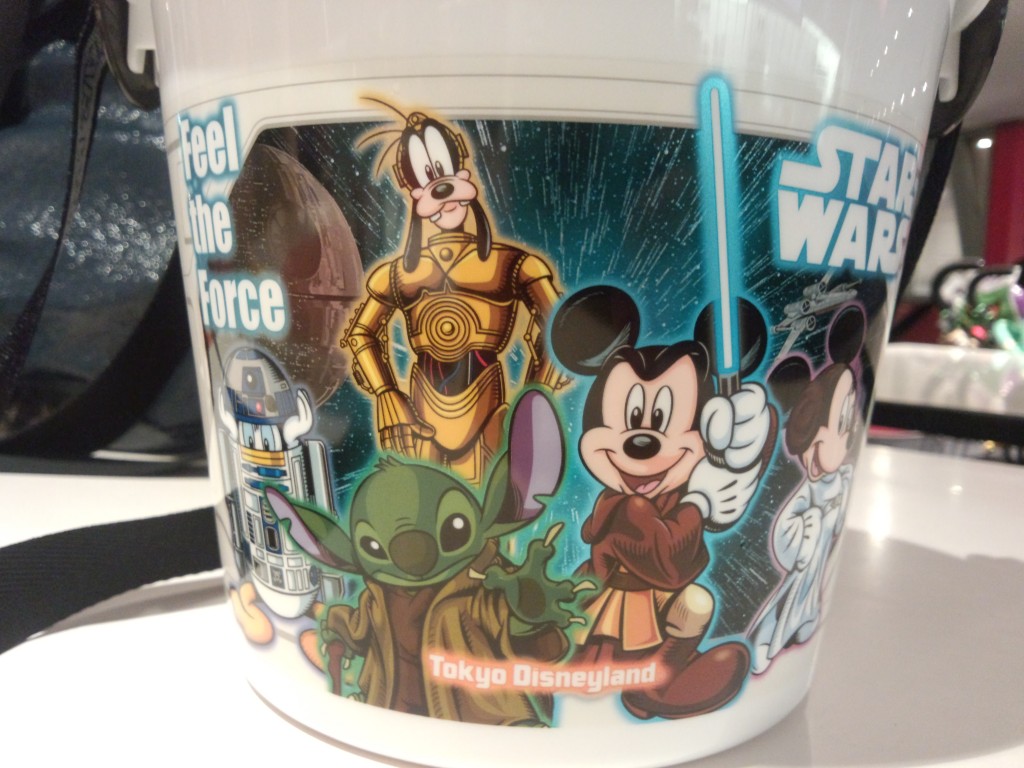

Almost everybody who goes to Tokyo Disneyland buys a commemorative popcorn bucket (or at least, Japanese people do). We went with the Star Wars one, sold near Star Tours.

The Star Wars characters have been “Disney-fied” with mostly core Disney characters, but notice the Stitch Yoda – a key indication this was made for Japan (other than the “Tokyo Disneyland” logo) – for no particular reason that I can discern, Stitch is considered incredibly cute in Japan and is very popular among Japanese Disney fans, as evidenced here.

The Haunted Mansion, decked out specially for its Halloween season-only Nightmare Before Christmas conversion. They really went all out with the conversion, and it felt really well done.

Notice, however, how dark it is outside. This isn’t because my camera’s bad at taking pictures at night or the Haunted Mansion is kept purposefully dark – the whole park is incredibly dark after sunset – as in, you won’t be able to see the face of the person standing next to you. It would be nice if they put a few more lights in.

The 30th Anniversary decoration at the entrance to the park.

I had to buy the senbei-styled tin. It’s the perfect mix of Japanese and Disney.

My girlfriend, knowing my love for Coke, bought me this special 30th Anniversary Coke. Inside is a special 30th Anniversary Coke bottle, and supposedly they didn’t make that many (which means, what, only 20,000 or so?).